Securing a future for koalas - chlamydia vaccine trial begins in south-west Sydney

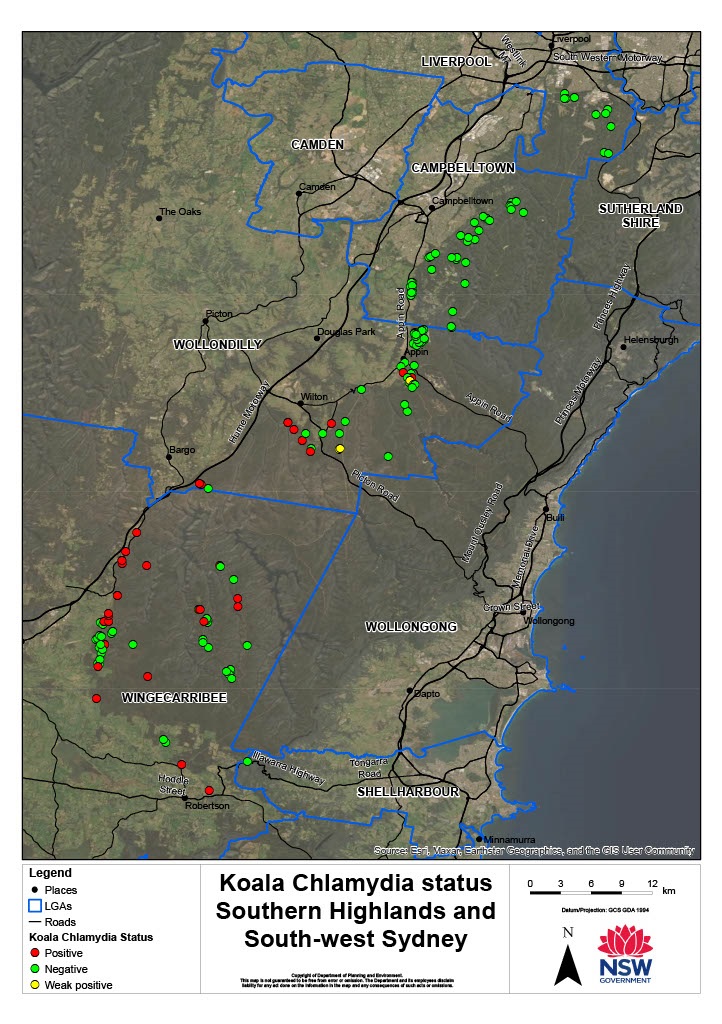

South-west Sydney is home to the largest growing population of koalas in the Sydney area. The population is estimated to be between 600 and 1,000 individuals and its success is thought to be related to the absence of chlamydia disease, otherwise known as chlamydiosis. However, chlamydia has now been detected in koalas less than 5 km from Campbelltown, increasing the risk of transmission as the population continues to grow and move about. Due to this and the population’s unique significance, the local government areas (LGAs) of Campbelltown, Wollondilly and Wingecarribee will be the focus of intensive intervention and investment to mitigate threats under the NSW Koala Strategy.

Why do we need a chlamydia vaccine?

A key factor in ensuring the ongoing health of koalas in the region is preventing the spread of chlamydiosis. Chlamydiosis is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia pecorum, and is a serious issue for koalas, causing significant pressure to many populations throughout the state. The disease causes infertility particularly in female koalas, but also can make koalas blind, weak and more susceptible to dog attacks and other threats such as extreme weather events like drought or severe heat.

While no koalas within Campbelltown LGA have tested positive for chlamydia, several chlamydia-positive koalas have recently been detected less than 5 km south in Appin. Local wildlife carers have reported koalas walking from Appin to Heathcote Road, highlighting the real and immediate risk to the Campbelltown population. The impact of chlamydiosis could be devastating for Campbelltown koalas given they have not been exposed to the disease in the past.

What is involved in the vaccination trial?

To address these issues, the NSW Government is investing more than $600,000 towards keeping the Campbelltown koala population free from chlamydiosis, including undertaking a vaccination trial. The trial is currently underway and led by the University of Sydney in collaboration with the University of the Sunshine Coast. The trial is also being supported by koala carers.

The vaccine has been tested extensively in koala hospital and rehabilitation settings and has been found to be safe. It has also been shown to effectively induce an immune response to chlamydiosis in these controlled environments, which should reduce susceptibility to chlamydiosis. The next step in the vaccine program is to test the effectiveness of the vaccine in wild koalas.

The vaccination program in south-west Sydney and the Southern Highlands has been designed with 2 aims:

to determine how the vaccine performs in wild populations, and

to collect information on its effectiveness and longevity.

If the vaccine performs successfully in this setting, additional koalas may be vaccinated in the Wollondilly area to form a chlamydiosis-free buffer between the Campbelltown and Southern Highlands koala population.

Koalas were located using infrared drones and captured by specially trained tree-climbing koala catchers in line with stringent animal ethics guidelines approved by a committee. Veterinarians from the University of Sydney have vaccinated koalas against chlamydiosis and the research team will track them using very high frequency (VHF) tracking collars to monitor their health over the coming years.

In the Southern Highlands, where chlamydiosis is present, 26 koalas have been vaccinated (or given a placebo) and GPS collared to see how effective the vaccine is in generating an immune response in koalas in the wild which are already coming in contact with chlamydia. Within Campbelltown LGA 10 koalas have been vaccinated and GPS collared and their immune response to the vaccine will be monitored over time. This is important to understand the response of wild koalas to the vaccine that have never been exposed to chlamydia to see how protective the vaccine is likely to be.

Results of the trial will not be known for several years. However, if it is successful, the vaccine will make koala populations more resilient to chlamydia infection and create a buffer zone around the significant Campbelltown koala population and help ensure a future for koalas in this area.

For more information:

Visit Koala Health Hub or contact Professor Peter Timms, University of the Sunshine Coast, at [email protected].